Spoiler alert! You should only proceed to read this article if you have already watched the movie, or simply don’t care about having the plot revealed.

Blade Runner 2049 is one of my most anticipated movies of 2017. I’ve always loved the original Blade Runner (1982) for its atmospheric portrayal, and rather dystopian prediction, of a potential future society. It dealt with some challenging philosophical questions such as existentialism, identity and individuality. Blade Runner (1982) was also visually stunning with its breathtaking city-scapes and incredibly detailed sets and props. So, how does 2049 manage to pick up the legacy left behind by its cult-status predecessor? In my opinion, it does so in a masterful and intellectual way.

True Science Fiction

2049 is a true science fiction movie. Often, we see that description used on anything that remotely contains elements of “future” or spaceships of some sort. In fact, and I’m pretty sure I’m right on this one, a true “science fiction” narrative is a one that envisions our future with an emphasis on society and humanity – and it examines the influence of technology on these core concepts. In doing so, it becomes a “fantastic” depiction of a future society that “could be”, whilst truly being a reflective commentary on the present day. This is exactly what the original movie did, and 2049 is no different as it dives even deeper into these core concepts. It explores and challenges our ideas of what it means to be an individual. What is it that defines a living human being? How do we decide whether something is merely A.I. (artificial intelligence) or a conscious being in possession of a soul? When all exterior, as well as interior, qualities are present, how do we make that distinction? This is the governing dilemma that lies at the core of the Blade Runner mythos.

Expanding the World

2049 paints an effective picture of a dystopian world that from afar seems like a sleeping giant, but once you get closer, you sense the myriad of life that exists in the endless streets that appear like mere cracks on the surface of this dense city-scape. Down here, underneath the carpet of smog and high-risers, you find the familiar neon-lit cyber-punk setting that we can recall from our previous encounter.

Being exposed to new locations of this dystopian world is one of the main attractions of 2049. As could be expected, the “Greater” Los Angeles area provides the main setting of this narrative, however, new locations such as the San Diego “garbage dump” and the radioactive wasteland of Las Vegas are explored too. Jared Leto’s character, Niander Wallace, even suggests the existence of “nine worlds” – most likely the, almost, mythological “Off-world” locations only hinted at in both the original movie as well as in 2049.

Experiencing the visual effects and the remarkable aesthetics of the world portrayed in 2049 is one of the joys of watching this movie. Despite its cold and harsh environment, it is a tangible world that is hard not to be enthralled by. However, I also feel that much credit must be given to the original Blade Runner (1982) since its neo-noir street-level portrayal of the universe still echoes in the back of your head when watching 2049.

Human or Replicant?

When I first watched Blade Runner (1982) I never stopped to consider whether Deckard was a replicant. It was a mind-boggler that was first raised in the wake of watching the movie, and it turned everything upside-down. 2049 embraces this conundrum full-heartedly and by going beyond the good old Nexus 6 with the inclusion of a 7th, 8th and 9th generation of replicants you become inherently suspicious of everything (and everyone) you see.

The plot unfolds through the eyes of K (Ryan Gosling), a Nexus 9 replicant. This makes 2049 quite different to the original movie in that we are fully aware of his replicant nature from the very beginning. As you follow K in his quite literal soul search, you wonder whether his actions and apparent motivations indicate the presence of an actual free will. I find that Ryan Gosling is a great cast here. He manages to portray the cool composure you’d expect from a replicant, but at the same time, you can sense the inner conflict in his eyes. Particularly his outburst during his interview with Dr. Ana Stelline is a shocking display of emotion that caught me off-guard. It is a powerful scene that really shows how troubled his mind is – a very human character trait.

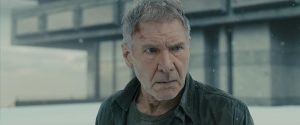

Seeing Harrison Ford return as Rick Deckard is also a pure delight. Compared to some of his other iconic roles, that of Deckard, to me, seems more intimate, and he displays a range of human emotions; desire, love, vulnerability – quite ironical if he’s indeed a replicant. Ford delivers a very strong performance that contains more emotion than what we are used to seeing from him. As was the case with Blade Runner (1982), there are a lot of relatively quiet scenes in 2049. Often, it is the moments between each line that really convey the feelings and emotion in the scene and it is refreshing to see Ford bring out such a performance.

Other noteworthy characters are those of Niander Wallace and Joi. I personally am a fan of Jared Leto, and his portrayal of the cynical Niander Wallace is interesting. His character doesn’t get that much screen-time, but once he does, he is a both terrifying and fascinating acquaintance. However, by the end of the movie, his driven character, with a bad case of God-complex, remains mostly shrouded in mystery.

Joi was one of the biggest surprises of 2049. The character is played by Ana de Armas, and she does a great job. She is one of the characters that I find intriguing. She’s also an A.I., but a simpler version of one. She even goes to explain the difference between herself and a replicant such as K, when describing herself as being made up of binary ones and zeros, whereas he is made up of synthetic DNA. It is difficult to tell if her character in fact does display an element of free will or if she is simply following her programming. I would argue that she does show early signs of self-awareness and a desire to pursue her own path. She displays an inherent, almost child-like, curiosity to the outside world and is protective of K. However, towards the end, when K is looking at the giant-sized Joi-advertisement, it is revealing to her programming that it addresses him as “Joe”, the same name that he was given by his own Joi-companion – a name that immediately makes me think of the expression “average Joe”.

Not So Much Noir

One thing that I missed a little when watching 2049 was the noir-element. To be frank, I don’t consider 2049 a noir at all. The original Blade Runner had a lot of these noir-elements, e.g. the soundtrack, the dark imagery and wide-spread use of silhouettes and shadows, the solitude of Deckard and even the voice-over parts, if you watched the theatrical cut. These elements established a strong noir-feel to the overall narrative. 2049 goes in a different direction, and even though the setting and atmosphere is the same, these noir-elements are not as present. The music is still in the vein of Vangelis’ epic score, but it lacks the defining melodies, including the melodic saxophone or piano tracks. Instead, the music is more modern and seeks to enhance the imagery more directly. Even though you do get the feeling that K is a loner, he does have Joi to keep him company most of the time too.

So, overall, I consider 2049 to be a quite different styled movie. It still has a nice slow pace, and there is plenty of time for reflection, but the obvious signs of noir are downplayed. It doesn’t hurt the movie, as such. It could even have been received a bit tacky to force those elements into this modern continuation.

With a Twist

I was instantly dragged into the story, and I didn’t spend a moment trying to figure out the puzzle. This also meant that I was often surprised by the development of the story – to me the plot was certainly not predictable.

The film takes its time to establish itself. I liked that we had time to familiarize ourselves with K, and let it be his story. Over the course of the movie, however, the story expands, and he gracefully becomes a piece of a larger whole and a larger conflict.

The plot of 2049 expands on the core concepts of Blade Runner in an ingenious way. It casts the original movie into an entirely different light, by revealing the fate of Rachael and Deckard. Once again, it challenges our notions of what it means to be human, to be a living being and to have a soul. The fact that Rachael was child-bearing, and eventually gave birth, makes her more human than ever. So, once again, we find that the definitions we perceived as adequate to distinguish them from us are severely inadequate, to the point of being completely obliterated.

The ending caught me off-guard too. I think I have developed this inherent expectation that when a story is revisited years later, but includes the original cast members, the plot will seek to pass the torch to the new generation – in this case K. I would never have expected that Deckard would be reunited with his “lost” child. This made the ending even more beautiful to me, and to see Harrison Ford portray the emotion within Deckard upon casting his eyes on the child that he had been forced to let go of so many years ago – it really made an impression on me.

It remains unclear whether K actually dies in the end. However, I find that there is stronger evidence to suggest that he does. In particular, the poetic throwback to the original movie with the familiar “Tears In Rain”-theme is used to frame the final moments of 2049 as the snow is falling down on K. “Tears In Rain” is the beautiful composition that accompanies Roy Batty’s memorable final monologue as he finally dies with the rain pouring down on him. I find this to be the strongest indication as to what happens with K.

Also, the falling snow is interesting as it traditionally, in a literary context, carries some form of symbolic meaning. It can symbolize both “the end” or even death. It can, however, also symbolize purity and rebirth. K decides to stay outside, on the stairs, and in his case, I find that the snow, as it falls on his face, symbolizes his death. Additionally, I find it noteworthy that he does not enter the building – the sanctuary – of Dr. Ana Stelline; a character that I associate with innocence and purity. It is as if he does not wish to defile that which is pure, and thus, all the violence, the blood and the suffering that has led to this point is left by the doorstep.

What Is on the Other Side of the Door?

2049 leaves audiences with quite a few unanswered questions. What will happen with the larger conflict between the replicant underground movement? Will Deckard and Ana Stelline spearhead the rebellion? What will the next step of Niander Wallace be? Is Deckard a replicant? Despite of these questions remaining without answer, I find the ending of 2049 to be beautiful and poetic. I sincerely hope that if there will ever be a sequel to 2049 that it will not go all-out on the brooding war between replicants and humans. We have other franchises that deliver that. To me, Blade Runner is about the philosophical questions. It looks more inwards than outwards. I doubt that we’ll see an actual francization of the Blade Runner universe. That is simply not a recipe that fits on the Blade Runner mythos and the style of narration we see in the two movies.

In Conclusion

2049 is a beautiful shot and written story. It honors the core concepts of its predecessor and it is a love-letter to the hardcore fans of the original movie. It continues the remarkable art-style of the original, and it continues the tradition of utilizing real-world objects in terms of sets and props. It manages to tell an engaging and thought-provoking story. The cast is phenomenal and there is depth to most, if not all, the characters that are portrayed.

Most importantly, it manages to stand on its own. Despite its deep roots in the original movie, 2049 has a story of its own to tell. It sparks the ethical and existential discussion of what it means to be human and to have a soul. What is the soul? What is our personality? Some would say that the soul contains our personality – the essence of us – and that our personality is the sum of our experiences. If a replicant has memories and these memories influence the way they perceive the world, and they breath, eat, sleep, love, desire, feel and create poetry – and even life. How are they then anything less than human? Is it not hypocritical to claim that a replicant has no soul if our definition of what that is, is inadequate and flawed? Robin Wright’s character, Lieutenant Joshi, blatantly tells K that “you’ve been getting on fine without one.” There are two ways to interpret this comment. Is she somehow comforting him by saying that he need not worry about this since most people do not, themselves, exhibit any obvious possession of one? Or is she being cynical and determining that he does his job better without one? But how do we measure the soul or conclude that a replicant might not develop one? Ironically, in the original Blade Runner (1982), her predecessor, Bryant told Deckard: “The designers reckoned that after a few years they might develop their own emotional responses. You know, hate, love, fear, anger, envy.”

Eventually, Blade Runner becomes a tale about – not what it means to be a replicant, but – what it means to be human. True science fiction.

Awesome Chris. A wonderful review. I read another review where the writer criticised 2049 for not being original enough and mentioned Dark City as an example, very unfair. I think the movie stands up well on its own. In 2049 the character agent k was just perfectly played by Ryan Gosling and actually Batista was superb. Gaff was not as impressive as in the original. I think the original had better characters overall. Harrison Ford IMO was average and the plot could have excluded him. I thought the love affair between k and the AI was arguably equally as intruiging as the original Deckard and Rachal.. 2049 it’s said borrows from the movie Her. I did like J Leto but thought maybe his dialogue was not as strong as it could have been. I do think the original edges out 2049 in terms of dialogue and yes that noir feel in many scenes are lacking in 2049, but the sets were amazing and Deakins the creator has been tipped for an Oscar.. The pace of the film was maybe too slow and the movie too long for the average viewer. Overall it’s not a mainstream movie.. But still one if my favorite.., 8/10.. IMO.

Thanks a lot for the fine comment, Andre! I sure hope this movie gets a lot of awards so it can have some continued success. It deserves it.